Ike Clayton is a man who walks the blurred edges of Tombstone’s wildest years—a name spoken softly, somewhere between legend and rumor. Unlike the notorious figures of Wyatt Earp or Doc Holliday, whose stories are told in bright detail, Clayton lingers in the half-light, a cipher of the Arizona Territory’s lawless borderlands. There, in the dust and danger between Tombstone, Charleston, and the Mexican border, Clayton and his ilk thrived in the margins, their livelihoods as unpredictable as the arid desert wind.

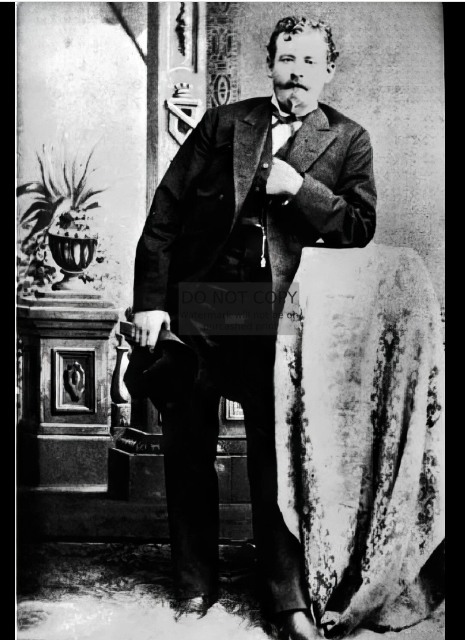

To picture a man like Clarke Clayton is to imagine someone neither entirely cowboy nor outright criminal, a figure more complicated than folklore often allows. On any given day, he might have been a ranch hand, a trail rider familiar with the rough life of the frontier—or, when opportunity knocked, a participant in the shadowy business of cattle rustling and stagecoach holdups. These so-called “Cow-Boys” of Cochise County were anything but innocent, notorious for brawls in saloons, for nights spent under the stars with bottles of whiskey, and for profiting from stolen herds driven up from Sonora. Clayton’s name is sometimes entwined with the likes of Curly Bill Brocius and the Clanton brothers, men whose rivalries with the law nearly defined the era, culminating in bullets and bloodshed like the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

What happened to Ike Clayton is anyone’s guess. Some say he met a violent end, as so many did in that unforgiving time. Others imagine him slipping away into Mexico, or simply disappearing as the frontier itself was tamed and the outlaw’s world faded into history. His story—fragmented, half-remembered—becomes part of the fabric of the American West. He is the ghost of a time when a man answered to his own code, when justice was as quick as a gunshot and as fleeting as a mirage on the horizon. In the end, Clayton remains not just a name, but a symbol of the toughness, the restlessness, and the stubborn defiance that still shapes our memory of the Wild West.