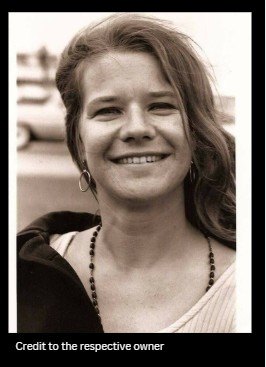

On the evening of October 3, 1970, Janis Joplin returned alone to Room 105 of the Landmark Motor Hotel in Hollywood. She had just picked up a pack of cigarettes from the front desk and briefly chatted with a clerk, who later described her as “friendly, but restless.” The hotel was quiet, and the echo of her boots in the hallway was one of the last sounds she made outside that room.

Earlier that day, she had called her road manager several times. She also phoned the front desk more than once, asked for a ride that never came, and waited in the lobby longer than anyone seemed to notice. Her Porsche, painted with wild psychedelic swirls, sat parked outside, untouched since she had driven in the night before. Janis wandered the hotel hallways, her eyes searching every face that passed. She looked expectant. She looked alone.

She had planned to record vocals for the track “Buried Alive in the Blues” the next day. The session was scheduled at Sunset Sound, and she had spoken enthusiastically about it in a phone call with her producer, Paul Rothchild. Her spirits seemed lifted, even cheerful. But as the hours passed and no one came, the excitement faded. Her final interactions—brief, polite, and empty—left a trail of unanswered questions.

Janis was used to crowds, adoration, and applause. She filled concert halls and burned through performances like a flame on gasoline. But when the shows ended, silence took over. Friends came and went. Lovers drifted away. Her voice, raw and magnificent on stage, had always concealed a fragility few understood. That night, with no one showing up, the silence returned.

She was known to be vulnerable to emotional swings. Rejection, even in small doses, cut deeply. She had been trying to reach an old friend that night, one who didn’t call back. There were also tentative plans with her on-again, off-again lover, Seth Morgan, but he stayed in San Francisco. These missed connections weren’t just practical disappointments; they mirrored a lifetime of craving connection and finding absence instead.

At one point that evening, she left her room again to get change for the cigarette machine. She passed a few hotel staff members, cracked a joke, and smiled. Then she walked back down the corridor with her shoulders slightly hunched and her head bowed in thought. The door to Room 105 closed behind her for the last time.

By morning, her band and crew grew worried when she missed the studio call. Road manager John Cooke arrived at the hotel and asked staff to open the door. Inside, he found her lying on the floor, clutching change in one hand. A half-smoked cigarette still sat in an ashtray, and a bottle of Southern Comfort was on the nightstand.

The coroner’s report later confirmed a heroin overdose. Her friends struggled to understand how someone so vibrant, so full of plans, had vanished overnight. But those who knew her closely had seen this possibility growing for months. It was never about one decision, one dose, or one bad night. It was years of invisible wounds, buried beneath fame, music, and the desperate need to belong.

Janis Joplin died at 27, surrounded by the silence she never wanted. That final night, spent dialing phones and walking alone through halls, was a heartbreaking echo of the loneliness she carried, even when the world was watching.

She left behind a room filled with music unsung, words unspoken, and a world that never truly saw her offstage.