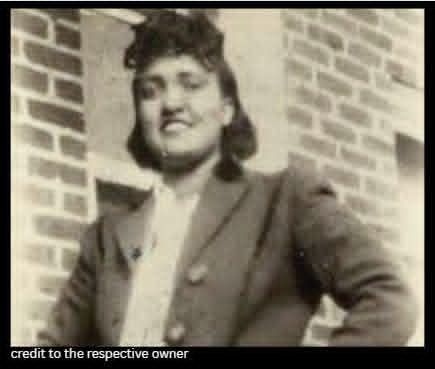

In 1951, 31-year-old Henrietta Lacks went to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for treatment of cervical cancer. During her care, doctors took samples of her tumor cells without her consent—a common practice at the time but one that later raised serious ethical concerns. Unlike normal human cells, which die after dividing a limited number of times, Lacks’ cells kept growing and dividing indefinitely in the lab. Named HeLa cells (from the first two letters of her first and last names), they became the world’s first immortal human cell line.

HeLa cells have since been crucial to modern medicine, aiding in the development of the polio vaccine, cancer treatments, in vitro fertilization, AIDS research, and even COVID-19 studies. They have been cloned, shared across laboratories, and multiplied into billions, all while Henrietta remained largely unknown to the public for decades.

Today, Henrietta Lacks is honored not only for her unwitting contribution to science but also as a powerful symbol in conversations about medical ethics, patient rights, and racial injustice in healthcare. Her story reminds us that behind every scientific breakthrough is a human life.